Maybe many of you have possibly never heard of MEL LEWIS - but Mel was one of those players that other drummers and musicians adored and hugely respected. He wasn't a showman or public hero like Gene Krupa (who mentored him when Mel was young), he wasn't a super soloist like Buddy Rich or Louie Bellson, but he could play - and he played brilliantly - always playing for the music itself, the band and the soloist.

Mel Lewis was a musicians musician - his musical integrity and ability to support, inspire and propel a band - be it a big band or small group was extraordinary. His partnership with the great trumpet man Thad Jones and their big band (and the subsequent band under how own leadership) was a mainstay of jazz brilliance for many years in New York, which inspired musicians from all over the world and was a magnet for young and established arrangers.

I had the great honour of meeting Mel Lewis in New York, when we talked about touring his big band in Europe, but sadly it wasn't meant to be. He was a lovely person and fascinating (especially for me as a drummer) to talk to.

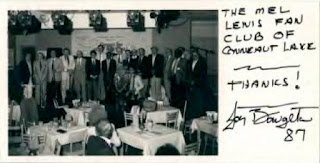

Chris Hill has written a superb book about the life of Mel Lewis and is very much worth reading. This photo library was introduced to me by Norbert Brecht and I am very grateful to Norbert for making me aware of this wonderful collection. Robert Méniere then kindly sent me this photographic collection, which has enabled me to write this blog. Huge thanks to Norbert and Robert (both members of the Great Drummers Group on FaceBook for anyone interested in drummers and the history of drumming). The photo collection (and videos, recordings etc) was donated by Doris Sokoloff in 1996 to the Miller Nichols Library at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. The following biography of Mel Lewis is thanks to www.dummerworld.com - a superb source of photos, videos and information on drummers.

Mel Lewis

- born Melvin Sokoloff in Buffalo, New York to Russian immigrant parents -

started playing professionally as a teen, eventually joining Stan Kenton in

1954.

His

musical career brought him to Los Angeles in 1957 and New York in 1963.

In 1966 in

New York, he teamed up with Thad Jones to lead the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis

Orchestra. The group started as informal jam sessions with the top studio and

jazz musicians of the city, but eventually began performing regularly on

Monday nights at the famed venue, the Village Vanguard. In 1979 the band won

a Grammy for their album Live in Munich.[1] Like all of the musicians in the

band, it was only a side line. In 1976, he released an album titled "Mel

Lewis and Friends" that featured him leading a smaller sextet that

allowed freedom and improvisation.

The band

became The Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, but when Jones moved to Denmark in

1978, it became known as Mel Lewis and the Jazz Orchestra. Lewis continued to

lead the band, recording and performing every Monday night at the Village

Vanguard until shortly before his death from cancer at age 60. The band still

performs on most Monday nights at the Village Vanguard; today it's known as

The Vanguard Jazz Orchestra and has released several CDs.

Mel Lewis's

cymbal work was unique and added qualities to his groups that are hard to

describe, but that are recognized immediately and virtually impossible to

emulate (Buddy Rich once said that "Mel Lewis doesn't sound like anybody

except himself"). He insisted on playing genuine Turkish-made cymbals,

switching from the Zildjian brand later in his career to the Istanbul brand.

His setup included a 21-inch ride on his right, an 19-inch crash-ride on his

left, and his signature sound, a 22-inch swish "knocker" with rivets

on his far right. The dark, overtone-rich sound of these rather lightweight

cymbals, combined with the rich, warm sound of his wood-shell drums (he

almost exclusively played Gretsch drums, although in later years was playing

Slingerland drums) equipped with natural calfskin top heads (again, Lewis was

a purist), using regular mylar heads on the bottom, exuded a veritable

treasure trove of sound. Lewis once described his playing philosophy of not

"pushing or pulling" but "supporting." "If you watch

me, it doesn't look like I'm doing much," he said in an interview,

describing his subtle but highly musical style. He could play at a break-neck

tempo for lengthy periods and hardly break a sweat. He wasn't flashy or

loud—just tasteful, and highly musical.

In the

late 1980s, Lewis was diagnosed with melanoma. He died on February 2, 1990,

just days before his band was to celebrate its 24th anniversary at the

Village Vanguard.

|

Talking

to Les Tompkins, 1971:

My home

town is Buffalo, New York; that's where I started playing drums—at three

years old, which is quite early. My father was a drummer, but he didn't want

me to be one. However, the drums were there in the house and as a baby, he

took me along wherever he played.

So that's

all I saw; I just loved them, right from the beginning. I started fooling

with them, he showed me how to hold the sticks, and that was it.

I played

all through elementary school; then, in high school, as I couldn't read music

I went on to the baritone horn. I learned quickly on that. That's how my

approach to what you'd call a more musical type of drumming came about; when

I see notes I don't think in terms of the drums. I think of that horn, and

I'm always concerned with the value of every note.

When I was

thirteen, I did my first professional job, with a trio at a dance hall in

Buffalo. And it just kept right on from there. At fifteen, I joined the

Musicians' Union and got with a big band.

Actually,

the big band thing started for me when I was about eight or nine years old.

For my last couple of years in school the music teacher gave me the job of

playing the whole set of drums with the whole school orchestra. There were a

lot of drummers who graduated, and I was all that was left. So she said:

"Would you like to tackle it that way, because I have nobody coming up

who's ready yet." It meant my handling eighty pieces.

Of course,

when I was into music professionally, there was a lot of small group

activity, too. Also the usual weddings and barmitzvahs situation which you go

through in a large city. There was nothing wrong with any of that, though; it

was all good, helpful experience.

I was playing

society music and all that, along with going out to jam, chasing all the

drummers, listening to everybody I could and learning from them. Because that

was the only way I could learn. I didn't have the formal training; I was

playing already. And whenever something changed, I wanted to hear it, to be

there to watch it and listen to it.

Buffalo

was a good stopping— off point from New York City. All the bands played there

regularly; bands played there regularly; also all the small bebop groups used

to come through to play breakfast dances and suchlike. I got to see Max Roach

and Art Blakey that way.

By the

time I was seventeen, I was already out on the road with a big band, working

in a territory out West. Then a year later I was in New York. I would say I'd

considered myself a bebopper from around sixteen on—which was 1945. That's

about the time it hit, anyway.

It was

with the Lennie Lewis band that I went to New York. He was a leader from

Buffalo who had a marvellous band; he picked up some great musicians when he

got to town, including several guys from the Duke Ellington band, who were

off at the time, as Duke had broken up and gone to Europe with a small group

for about six months. We played at the Savoy Ballroom and the Apollo Theatre.

Out of

that I ended up with the Boyd Raeburn band, followed by some commercial bands

for quite a while; Alvino Rey, Ray Anthony, Tex Beneke. But there were always

good jazzmen in each of these bands—up against the same thing as me: there

were only four major jazz bands going. Even then, it was just Duke, Basie,

Woody and Kenton.

Shelly

Manne was very busy with Kenton at the time, as were Don Lamond with Woody,

Gus Johnson with Basie and Sonny Greer with Duke. No openings anywhere.

And if

there were, I wouldn't have got the job, anyway, because I didn't have the

jazz reputation. Although I knew an awful lot of jazz musicians in New York;

I always made all the sessions, sat in everywhere I could.

This sort

of situation continued until '53, when Stan Levey was about to quit Kenton.

The band was preparing to go to Dublin and Levey wasn't going ta make that

trip; he'd got in a beef with Stan over something. I was playing with Beneke

in Detroit the same night. Kenton was there, and he sent somebody out to hear

me, because I'd been recommended by Maynard Ferguson, who'd been on the

Raeburn band with me.

Kenton

told his associate: "Don't listen to the band; just listen to him play,

and if you think he's strong enough to handle our music, have him come to see

me tomorrow." The guy did like me, we had the interview and he hired me.

Then Levey changed his mind, they made up and he decided to stay put; so I

remained with Beneke far a while, after which I rejoined Ray Anthony.

Sure

enough, though, Kenton lived up to his word: the next time Levey left, I took

over, and I stayed there three years.

The Kenton

band was a completely different thing to what I had done before, but I was

entirely ready and able to handle it. Right from the start, I had no trouble.

And, frankly, I thank working with all the commercial bands. Because—I'll

tell you something—a lot of young bebop drummers find it very difficult to

work with a big band. For obvious reasons: it's not an easy thing. Playing in

a jazz band, you have to be geared to create and to swing; it's dependent on

your taste, your feeling and your being a jazz musician. I would stress the

word musician.

Most of

the arrangements are much more intricate than in a commercial band; there's a

lot of things going on.

You have

to take over; also if you're a creative player, you want to do it your way.

Whereas in a commercial situation, it's simpler music, yet it's harder to

play in a lot of ways—because. there's not much you can do with it. The

musicianship in bands of that kind was generally fairly high, but there was

an attitude towards laziness. So being able to get something happening with a

commercial band made you strong. That's why it was such extremely good

experience.

If a young

drummer coming up gets a chance to play with a commercial band and he doesn't

want to do it, because its not musically stimulating for him, I tell him to

think twice about it. Any kind of commercial work can have this strengthening

effect.

That is,

if you also spend all your free time playing with the right musicians. Your

first love is jazz, but you must still be able to turn that other thing off

and on. Which is not easy; this is the reason the average drummer is not a

jazz drummer. Once the commercial thing takes you over, that's all you end up

doing.

The

trouble today is that it's much more of a problem to find somewhere to go out

and play. When I was younger, it was a lot easier.

By the

time I got to the Kenton band, in the early 'fifties, he had really started

stretching out; it was not quite Progressive Jazz, as it was called, any

more. He had Bill Holman writing for him, and he was leaning mare towards a

swinging sound. It wasn't as loud as before; the band was lighter and more

flowing. The soloists were more stimulated and they could swing harder.

The Boyd

Raeburn band, by comparison with that, had been more a concert band. A little

stiffer, too; they still played with the dotted eighths/sixteenths feel. But

it was a difficult and interesting book, nevertheless; it taught me a lot.

The Kenton book was more intricate, and the musicianship was even higher.

Plus the

welcome new direction he was taking, Actually, he went back to the

Progressive thing later. I feel that I was lucky; I happened to be part of

what I consider one of Kenton's best musical eras. We sort of call that the

Bill Holman band. That was really Bill's band in a lot of ways. He made it

become something marvellous.

From that

period to this day, Bill and I have been very close friends. I regard him as

one of the very greatest writers. In fact, as far as I'm concerned, on the

West Coast he is the best.

His writing

is just as individual as he is himself. Bill Holman is a very singular

person; he's not like anybody else I know. He has his own type of humour and

creative thinking.. He loves counterpoint and he really knows how to use it

in the most beautiful way.

Listing my

favourite arrangers, in no special order, it has to be Thad Jones, Bob

Brookmeyer and Bill Holman. These are three fantastic minds musically. I

think all three of them are completely underrated as arrangers. And that's

silly—because there's nobody better. In my opinion, anyway, but I believe a

lot of people are starting to agree with me.

Brookmeyer

has been a great writer for years, but not enough people seem to know about

him. He did one band album of his own, and he wrote most of the Gerry Mulligan

Concert Band book. The things he's written for our band are tremendous; a

beautiful change of pace from my partner Thad. Nobody can write for this band

better than Thad, but Bobby is the only one who can capture the band; he can

change the sound yet it still fits us.

It is

really Thad's band, though: from a rhythm standpoint, he's unique; Thad is

one of the most interesting drum writers I've ever known. His music is very

difficult to play. You have to be a high calibre musician to play Thad Jones

arrangements.

But when

they are played right, forget it!—there's nothing like it. I can't help

boasting about him, because as a writer, player, conductor and as a man, he

has no peer.

|

Tuesday, 23 August 2016

MEL LEWIS - A PHOTOGRAPHIC TRIBUTE TO THIS GREAT DRUMMER

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)